- Home

- Usman T. Malik

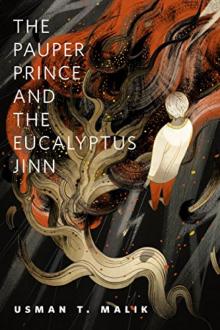

The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn: a Tor.com Original

The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn: a Tor.com Original Read online

The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn

By

Usman T. Malik

illustration by Victo Ngai

“The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn” copyright © 2015 by Usman T. Malik

Art copyright © 2015 by Victo Ngai

Publication Date: Wed Apr 22 2015 09:00am

A Tor Original

Introduction

“The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn” by Usman T. Malik is a fantasy novella about a disenchanted young Pakistani professor who grew up and lives in the United States, but is haunted by the magical, mystical tales his grandfather told him of a princess and a Jinn who lived in Lahore when the grandfather was a boy.

This novella was acquired and edited for Tor.com by consulting editor Ellen Datlow.

“When the Spirit World appears in a sensory Form, the Human Eye confines it. The Spiritual Entity cannot abandon that Form as long as Man continues to look at it in this special way. To escape, the Spiritual Entity manifests an Image it adopts for him, like a veil. It pretends the Image is moving in a certain direction so the Eye will follow it. At which point the Spiritual Entity escapes its confinement and disappears.

Whoever knows this and wishes to maintain perception of the Spiritual, must not let his Eye follow this illusion.

This is one of the Divine Secrets.”

The Meccan Revelations by Muhiyuddin Ibn Arabi

For fifteen years my grandfather lived next door to the Mughal princess Zeenat Begum. The princess ran a tea stall outside the walled city of Old Lahore in the shade of an ancient eucalyptus. Dozens of children from Bhati Model School rushed screaming down muddy lanes to gather at her shop, which was really just a roadside counter with a tin roof and a smattering of chairs and a table. On winter afternoons it was her steaming cardamom-and-honey tea the kids wanted; in summer it was the chilled Rooh Afza.

As Gramps talked, he smacked his lips and licked his fingers, remembering the sweet rosewater sharbat. He told me that the princess was so poor she had to recycle tea leaves and sharbat residue. Not from customers, of course, but from her own boiling pans—although who really knew, he said, and winked.

I didn’t believe a word of it.

“Where was her kingdom?” I said.

“Gone. Lost. Fallen to the British a hundred years ago,” Gramps said. “She never begged, though. Never asked anyone’s help, see?”

I was ten. We were sitting on the steps of our mobile home in Florida. It was a wet summer afternoon and rain hissed like diamondbacks in the grass and crackled in the gutters of the trailer park.

“And her family?”

“Dead. Her great-great-great grandfather, the exiled King Bahadur Shah Zafar, died in Rangoon and is buried there. Burmese Muslims make pilgrimages to his shrine and honor him as a saint.”

“Why was he buried there? Why couldn’t he go home?”

“He had no home anymore.”

For a while I stared, then surprised both him and myself by bursting into tears. Bewildered, Gramps took me in his arms and whispered comforting things, and gradually I quieted, letting his voice and the rain sounds lull me to sleep, the loamy smell of him and grass and damp earth becoming one in my sniffling nostrils.

I remember the night Gramps told me the rest of the story. I was twelve or thirteen. We were at this desi party in Windermere thrown by Baba’s friend Hanif Uncle, a posh affair with Italian leather sofas, crystal cutlery, and marble-topped tables. Someone broached a discussion about the pauper princess. Another person guffawed. The Mughal princess was an urban legend, this aunty said. Yes, yes, she too had heard stories about this so-called princess, but they were a hoax. The descendants of the Mughals left India and Pakistan decades ago. They are settled in London and Paris and Manhattan now, living postcolonial, extravagant lives after selling their estates in their native land.

Gramps disagreed vehemently. Not only was the princess real, she had given him free tea. She had told him stories of her forebears.

The desi aunty laughed. “Senility is known to create stories,” she said, tapping her manicured fingers on her wineglass.

Gramps bristled. A long heated argument followed and we ended up leaving the party early.

“Rafiq, tell your father to calm down,” Hanif Uncle said to my baba at the door. “He takes things too seriously.”

“He might be old and set in his ways, Doctor sahib,” Baba said, “but he’s sharp as a tack. Pardon my boldness but some of your friends in there . . .” Without looking at Hanif Uncle, Baba waved a palm at the open door from which blue light and Bollywood music spilled onto the driveway.

Hanif Uncle smiled. He was a gentle and quiet man who sometimes invited us over to his fancy parties where rich expatriates from the Indian subcontinent opined about politics, stocks, cricket, religious fundamentalism, and their successful Ivy League–attending progeny. The shyer the man the louder his feasts, Gramps was fond of saying.

“They’re a piece of work all right,” Hanif Uncle said. “Listen, bring your family over some weekend. I’d love to listen to that Mughal girl’s story.”

“Sure, Doctor sahib. Thank you.”

The three of us squatted into our listing truck and Baba yanked the gearshift forward, beginning the drive home.

“Abba-ji,” he said to Gramps. “You need to rein in your temper. You can’t pick a fight with these people. The doctor’s been very kind to me, but word of mouth’s how I get work and it’s exactly how I can lose it.”

“But that woman is wrong, Rafiq,” Gramps protested. “What she’s heard are rumors. I told them the truth. I lived in the time of the pauper princess. I lived through the horrors of the eucalyptus jinn.”

“Abba-ji, listen to what you’re saying! Please, I beg you, keep these stories to yourself. Last thing I want is people whispering the handyman has a crazy, quarrelsome father.” Baba wiped his forehead and rubbed his perpetually blistered thumb and index finger together.

Gramps stared at him, then whipped his face to the window and began to chew a candy wrapper (he was diabetic and wasn’t allowed sweets). We sat in hot, thorny silence the rest of the ride and when we got home Gramps marched straight to his room like a prisoner returning to his cell.

I followed him and plopped on his bed.

“Tell me about the princess and the jinn,” I said in Urdu.

Gramps grunted out of his compression stockings and kneaded his legs. They occasionally swelled with fluid. He needed water pills but they made him incontinent and smell like piss and he hated them. “The last time I told you her story you started crying. I don’t want your parents yelling at me. Especially tonight.”

“Oh, come on, they don’t yell at you. Plus I won’t tell them. Look, Gramps, think about it this way: I could write a story in my school paper about the princess. This could be my junior project.” I snuggled into his bedsheets. They smelled of sweat and medicine, but I didn’t mind.

“All right, but if your mother comes in here, complaining—”

“She won’t.”

He arched his back and shuffled to the armchair by the window. It was ten at night. Cicadas chirped their intermittent static outside, but I doubt Gramps heard them. He wore hearing aids and the ones we could afford crackled in his ears, so he refused to wear them at home.

Gramps opened his mouth, pinched the lower denture, and rocked it. Back and forth, back and forth. Loosening it from the socket. Pop! He removed the upper one similarly and dropped both in a bowl of warm water on the table by the armchair.

I slid off the bed. I went to hi

m and sat on the floor by his spidery, white-haired feet. “Can you tell me the story, Gramps?”

Night stole in through the window blinds and settled around us, soft and warm. Gramps curled his toes and pressed them against the wooden leg of his armchair. His eyes drifted to the painting hanging above the door, a picture of a young woman turned ageless by the artist’s hand. Soft muddy eyes, a knowing smile, an orange dopatta framing her black hair. She sat on a brilliantly colored rug and held a silver goblet in an outstretched hand, as if offering it to the viewer.

The painting had hung in Gramps’s room for so long I’d stopped seeing it. When I was younger I’d once asked him if the woman was Grandma, and he’d looked at me. Grandma died when Baba was young, he said.

The cicadas burst into an electric row and I rapped the floorboards with my knuckles, fascinated by how I could keep time with their piping.

“I bet the pauper princess,” said Gramps quietly, “would be happy to have her story told.”

“Yes.”

“She would’ve wanted everyone to know how the greatest dynasty in history came to a ruinous end.”

“Yes.”

Gramps scooped up a two-sided brush and a bottle of cleaning solution from the table. Carefully, he began to brush his dentures. As he scrubbed, he talked, his deep-set watery eyes slowly brightening until it seemed he glowed with memory. I listened, and at one point Mama came to the door, peered in, and whispered something we both ignored. It was Saturday night so she left us alone, and Gramps and I sat there for the longest time I would ever spend with him.

This is how, that night, my gramps ended up telling me the story of the Pauper Princess and the Eucalyptus Jinn.

The princess, Gramps said, was a woman in her twenties with a touch of silver in her hair. She was lean as a sorghum broomstick, face dark and plain, but her eyes glittered as she hummed the Qaseeda Burdah Shareef and swept the wooden counter in her tea shop with a dustcloth. She had a gold nose stud that, she told her customers, was a family heirloom. Each evening after she was done serving she folded her aluminum chairs, upended the stools on the plywood table, and took a break. She’d sit down by the trunk of the towering eucalyptus outside Bhati Gate, pluck out the stud, and shine it with a mint-water-soaked rag until it gleamed like an eye.

It was tradition, she said.

“If it’s an heirloom, why do you wear it every day? What if you break it? What if someone sees it and decides to rob you?” Gramps asked her. He was about fourteen then and just that morning had gotten Juma pocket money and was feeling rich. He whistled as he sat sipping tea in the tree’s shade and watched steel workers, potters, calligraphers, and laborers carry their work outside their foundries and shops, grateful for the winter-softened sky.

Princess Zeenat smiled and her teeth shone at him. “Nah ji. No one can steal from us. My family is protected by a jinn, you know.”

This was something Gramps had heard before. A jinn protected the princess and her two sisters, a duty imposed by Akbar the Great five hundred years back. Guard and defend Mughal honor. Not a clichéd horned jinn, you understand, but a daunting, invisible entity that defied the laws of physics: it could slip in and out of time, could swap its senses, hear out of its nostrils, smell with its eyes. It could even fly like the tales of yore said.

Mostly amused but occasionally uneasy, Gramps laughed when the princess told these stories. He had never really questioned the reality of her existence; lots of nawabs and princes of pre-Partition India had offspring languishing in poverty these days. An impoverished Mughal princess was conceivable.

A custodian jinn, not so much.

Unconvinced thus, Gramps said:

“Where does he live?”

“What does he eat?”

And, “If he’s invisible, how does one know he’s real?”

The princess’s answers came back practiced and surreal:

The jinn lived in the eucalyptus tree above the tea stall.

He ate angel-bread.

He was as real as jasmine-touched breeze, as shifting temperatures, as the many spells of weather that alternately lull and shake humans in their variegated fists.

“Have you seen him?” Gramps fired.

“Such questions.” The Princess shook her head and laughed, her thick, long hair squirming out from under her chador. “Hai Allah, these kids.” Still tittering, she sauntered off to her counter, leaving a disgruntled Gramps scratching his head.

The existential ramifications of such a creature’s presence unsettled Gramps, but what could he do? Arguing about it was as useful as arguing about the wind jouncing the eucalyptus boughs. Especially when the neighborhood kids began to tell disturbing tales as well.

Of a gnarled bat-like creature that hung upside down from the warped branches, its shadow twined around the wicker chairs and table fronting the counter. If you looked up, you saw a bird nest—just another huddle of zoysia grass and bird feathers—but then you dropped your gaze and the creature’s malignant reflection juddered and swam in the tea inside the chipped china.

“Foul face,” said one boy. “Dark and ugly and wrinkled like a fruit.”

“Sharp, crooked fangs,” said another.

“No, no, he has razor blades planted in his jaws,” said the first one quickly. “My cousin told me. That’s how he flays the skin off little kids.”

The description of the eucalyptus jinn varied seasonally. In summertime, his cheeks were scorched, his eyes red rimmed like the midday sun. Come winter, his lips were blue and his eyes misty, his touch cold like damp roots. On one thing everyone agreed: if he laid eyes on you, you were a goner.

The lean, mean older kids nodded and shook their heads wisely.

A goner.

The mystery continued this way, deliciously gossiped and fervently argued, until one summer day a child of ten with wild eyes and a snot-covered chin rushed into the tea stall, gabbling and crying, blood trickling from the gash in his temple. Despite several attempts by the princess and her customers, he wouldn’t be induced to tell who or what had hurt him, but his older brother, who had followed the boy inside, face scrunched with delight, declared he had last been seen pissing at the bottom of the eucalyptus.

“The jinn. The jinn,” all the kids cried in unison. “A victim of the jinn’s malice.”

“No. He fell out of the tree,” a grownup said firmly. “The gash is from the fall.”

“The boy’s incurred the jinn’s wrath,” said the kids happily. “The jinn will flense the meat off his bones and crunch his marrow.”

“Oh shut up,” said Princess Zeenat, feeling the boy’s cheeks, “the eucalyptus jinn doesn’t harm innocents. He’s a defender of honor and dignity,” while all the time she fretted over the boy, dabbed at his forehead with a wet cloth, and poured him a hot cup of tea.

The princess’s sisters emerged from the doorway of their two-room shack twenty paces from the tea stall. They peered in, two teenage girls in flour-caked dopattas and rose-printed shalwar kameez, and the younger one stifled a cry when the boy turned to her, eyes shiny and vacuous with delirium, and whispered, “He says the lightning trees are dying.”

The princess gasped. The customers pressed in, awed and murmuring. An elderly man with betel-juice-stained teeth gripped the front of his own shirt with palsied hands and fanned his chest with it. “The jinn has overcome the child,” he said, looking profoundly at the sky beyond the stall, and chomped his tobacco paan faster.

The boy shuddered. He closed his eyes, breathed erratically, and behind him the shadow of the tree fell long and clawing at the ground.

The lightning trees are dying. The lightning trees are dying.

So spread the nonsensical words through the neighborhood. Zipping from bamboo door-to-door; blazing through dark lovers’ alleys; hopping from one beggar’s gleeful tongue to another’s, the prophecy became a proverb and the proverb a song.

A starving calligrapher-poet licked his reed quill and wrote an elegy for the

lightning trees.

A courtesan from the Diamond Market sang it from her rooftop on a moonlit night.

Thus the walled city heard the story of the possessed boy and his curious proclamation and shivered with this message from realms unknown. Arthritic grandmothers and lithe young men rocked in their courtyards and lawns, nodding dreamily at the stars above, allowing themselves to remember secrets from childhood they hadn’t dared remember before.

Meanwhile word reached local families that a child had gotten hurt climbing the eucalyptus. Angry fathers, most of them laborers and shopkeepers with kids who rarely went home before nightfall, came barging into the Municipality’s lean-to, fists hammering on the sad-looking officer’s table, demanding that the tree be chopped down.

“It’s a menace,” they said.

“It’s hollow. Worm eaten.”

“It’s haunted!”

“Look, its gum’s flammable and therefore a fire hazard,” offered one versed in horticulture, “and the tree’s a pest. What’s a eucalyptus doing in the middle of a street anyway?”

So they argued and thundered until the officer came knocking at the princess’s door. “The tree,” said the sad-looking officer, twisting his squirrel-tail mustache, “needs to go.”

“Over my dead body,” said the princess. She threw down her polish rag and glared at the officer. “It was planted by my forefathers. It’s a relic, it’s history.”

“It’s a public menace. Look, bibi, we can do this the easy way or the hard way, but I’m telling you—”

“Try it. You just try it,” cried the princess. “I will take this matter to the highest authorities. I’ll go to the Supreme Court. That tree”—she jabbed a quivering finger at the monstrous thing—“gives us shade. A fakir told my grandfather never to move his business elsewhere. It’s blessed, he said.”

The sad-faced officer rolled up his sleeves. The princess eyed him with apprehension as he yanked one of her chairs back and lowered himself into it.

#Spring Love, #Pichal Pairi

#Spring Love, #Pichal Pairi The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn: a Tor.com Original

The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn: a Tor.com Original